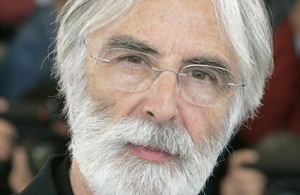

Everything about Michael Haznavicius’ The Artist, a silent film about silent film, is undeniably lovely. Just like its star, the fictional actor George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), it glows off the screen in crisp black and white, winking and smiling, charming the audience with unfettered nostalgia and an irrepressible sense of romance. Its own cultural life has been equally pleasing – building momentum from a last-minute addition to competition at Cannes to considerable critical acclaim and an emergence as the unlikely front-runner for the best picture Oscar in February. It even has a cute dog.

To watch The Artist is to be frequently delighted: by skillful physical expression, clever visual tricks and well-timed taps of feet. Its centrepiece is a wonderful sequence in which Valentin encounters the young starlet Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo) on a film shoot and, distracted, fails to complete the scene, returning numerous times to his starting pose with an inch-perfect thespy frown. We know Haznavicius knows this scene is good, because he reprises it later on. Miller, now a megastar to Valentin’s has-been, recognises and recalls the moment through examining a film reel – something, of course, you couldn’t do today.

But if this is film which – as many critics would have it – is supposed to be celebrating a bygone era, or lamenting a purity lost with the move to sound, it’s not particularly convincing, or consistent. I found myself pondering how silent acting (i.e. mime), and by extension silent storytelling, seem to necessitate a certain broadness of tone. Whilst I enjoyed almost everything that appeared on screen, I was rarely engaged on a level that went beyond amusement.

Indeed, two instances which did have genuine power occurred when sound interjected: firstly, subtly, with the tap of glass on a table during the doubting Valentin’s lurid dream; then, most stirringly of all, through the oh-so human panting of the two performers after a celebratory final dance. The film loads these moments with pure electricity by strength of contrast – so what’s Haznavicius telling us? Not, if anything, about what was lost, but about the excitement of a moment in history. Film was now able to transfix us further, adding nuance and complexity beyond the limit of an orchestral score throughout.

In fact, as it happens, I don’t think The Artist is nearly weighty enough to carry anything so serious as a manifesto, one way or the other. Essentially it’s a brilliant gimmick: a feat of showmanship and a masterclass in charm, pulled off with aplomb. You know there’ll be a happy ending, because you know the film just wants you to be entertained. It’s all the better for it.